A Closer Look At Personas: A Guide To Developing The Right Ones (Part 2)

How can designers create experiences that are custom tailored to people who are unlike themselves? As explained in part 1 of this series, an effective way to gain knowledge of, build empathy for and sharpen focus on users is to use a persona. This final part of the series will explain an effective method of creating a persona.

There are myriad ways to integrate user-centered thinking into the creative process of UX design, and personas are one of the most effective ways to empathize with and analyze users. There is no one right way to develop a persona, but the method I will share here is based on processes developed, field-tested and refined over the years at the interaction design agency Cooper.

This process follows a logical order that begins with knowing nothing (or very little) about users and ends with a refined and nuanced perspective of users that can be shared with others.

1. Identify Your Users

Before you can learn from people, you need to decide whom to learn from. You could create a screener based on demographics and psychographics to determine who to observe and talk to and who not to.

Traditional research on market segmentation is a good place to start. If a user base is already established, then you might have a source of data on demographics; if there is no such source, then you could send out surveys to current users to obtain more information. If you have no user base (which will be the case if your company is new), then find out more about the users of your competitors or of similar companies or products.

2. Decide What To Ask

The most common way to learn from users is to interview and/or observe them. An interview script or research protocol will ensure that you obtain the same information from all research subjects, so that the data set is homogeneous. The process of developing a script or protocol forces you to think about what you will need to learn from research participants. Interviews and observation aren’t just about acquiring raw data, but about gaining a thorough understanding of participants and their perspectives.

Learning everything about participants is impossible within the limited time available for interviews and observation, so try to ask the most advantageous questions and observe the most relevant behavior. To determine what information is most needed, think of your knowledge gaps, which details would best inform your design decisions, what your team members are curious about, and what would give the team a common frame of reference regarding the participants’ needs and goals.

The questions and areas of observation need not be exhaustive at this stage, because the goal is to gain a fundamental understanding of users, from which the team can extrapolate in future and answer new questions on their own. By thoroughly understanding users, team members should be able to put on the persona’s shoes and walk in uncharted territory. Users won’t have a seat at the table during the product’s development, but a persona created from the right kind of information is the best proxy. By capturing the essence of their perspectives from asking the right questions, you will be able to create a persona that brings their voice into the conversation.

The exact questions you ask will vary according to the project’s goals, the types of people being interviewed or observed, and the time constraints. No matter what you ask, though, keep the following in mind:

- Ask primarily open-ended questions.

- Ask participants to show more than tell.

- When possible, ask for specific stories, especially about anything you cannot observe.

Don’t be afraid to ask seemingly naïve questions either because you’ll want to find out as much as possible. (Naïve questions are never stupid; they show an eagerness to learn, and they establish a non-authoritative tone in the interview, which is great for building rapport with participants.) Following these guidelines will result in a rich set of answers and a firm foundation on which to build a persona.

You could create your own interview script from the following template, which I have used in many enterprise software design projects. I have found it quite useful as a jumping-off point in new projects.

Overview

- Give us a little background on your job.

- How and why did you take on this job?

- How long have you been working in this capacity?

- Why do you work for this company and not another?

- Tell me a bit about your industry and your role in it.

Domain Knowledge

- What skills are required to do your job?

- How do you stay up to date and get information on your industry and profession?

Goals

- What are your responsibilities in your job?

- How do you define progress or success in your job?

- How do you measure progress or success?

Attitudes And Motivations

- What are the most enjoyable parts of your job?

- What do you value most?

- Do you have any external (i.e. extrinsic) or internal (i.e. intrinsic) motivations for doing a good job (such as rewards, promotions, perks)?

Processes

- Describe a typical workday. What do you do when you first get into the office? What do you do next?

- How do you do [a certain task]?

- How long does this task typically take?

- Where would you start?

- What would you do next?

- Can you show me how you do that?

- What activities take up most of your time?

- What activities are most important to your success?

- Of the things you do during a typical workday, are any of those processes or tasks mandated by your company or industry?

- What processes have you developed on your own?

- Have you learned to work better from your colleagues?

Environment

- How is your office organized to help you accomplish your tasks or goals?

- Show me how you use your office to accomplish your tasks or goals?

Pain Points

- What are the most difficult, challenging, annoying or frustrating aspects of your job?

- After a typical workday, what about your job (if anything) is still on your mind? (In other words, what issues keep you up at night?)

Tools And Technology

- What traditional (i.e. analogue) tools do you use to accomplish tasks in your job?

- What digital tools do you use to accomplish tasks in your job?

- Where do any of your tools fall short? (What do you need them to do that they don’t do or don’t do well?)

Mental Models

- What kinds of people do well in your position? Why?

- Describe a process and how it has changed or not changed over time.

Relationships And Organizational Structure

- Besides clients and customers, who else do you interact with in your work?

- Who do you report to?

- Who reports to you?

- How often do you collaborate with others?

- How do you collaborate?

Projecting Into The Future

- If we came back in [x number of] years to have this conversation again, what would be different?

- If you could build your ideal experience, what would it be?

Wrapping Up

- Have we missed anything?

- Is there anything you want to tell us?

- Is there anything you want to ask us?

3. Get Access To Users

This step will largely determine how effective your personas are. Finding an adequate number of people will determine whether your personas are an accurate and useful representation of the research participants. Experts recommend finding anywhere from just 5 to around 30 participants per role. The exact number isn’t important, as long as trends and patterns emerge. These number might seem too small to be of any reliable use, but the data set isn’t intended for statistical analysis, but rather for qualitative analysis that will inform the design process.

Trends are often observable from just five people. Build on that to gain a deeper understanding. The number of participants does not matter as much as whether you gain new information from interviews and observation. The law of diminishing returns applies here; at a certain point, new interviews or further observation will elicit little to no new information because all relevant patterns have been unearthed and the researcher has reached a level of understanding known to ethnographers as “verstehen.” At this point, no more research is needed.

The benefit of observation in addition to interviews is that a relatively small number of participants is needed for it. If you can’t find enough people on your own or with help from people you know, then consider a recruiting agency.

4. Gain An Understanding Of Users

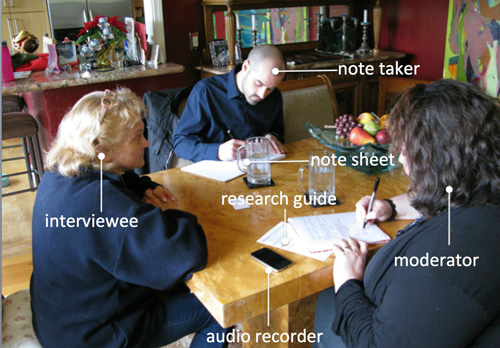

The majority of the process of creating personas is usually spent interviewing and observing people. Collaborate with another team member so that they capture anything in the interview or observation session that you might miss. You and your colleague should be physically present with the research participants, in a location that makes the most sense for the project. In a suitable location, participants tend to provide more detailed and accurate information and are less likely to behave unnaturally.

Direct, unfiltered interaction with participants is critical at this stage in order to gain empathy with the people you will be designing for. Being there in person is not always feasible, but try to do it whenever possible. If you can’t do that, then consider the next best thing: interviewing people who have had direct interaction with users. Personas created from secondhand information are called provisional personas. The perspectives will be secondhand, filtered and biased, but they’re better than nothing and you’ll have somewhere to start your research.

Empathy is important to understanding users holistically, and direct interaction is the only way to inform the heart as well as the mind. I’m not one to get touchy-feely for its own sake, but when you are able to empathize with users firsthand, they you’re better able to tap into their intuition and act on inklings that you otherwise would not have. Firsthand exposure is paramount.

5. Analyze The Data

The analysis stage is the most complicated because you must compare multiple variables of behavior and attitudes among many research participants. It requires some practice, and it gets much easier with experience. To find out more in depth, look at the descriptions in the Fluid project, or consider reading Designing for the Digital Age.

After learning about research participants directly or indirectly, you will need to make sense of it all by finding patterns in the data. In short, for each group of participants with the same role (for example, a group of doctors), you would rank each participant against a number of attributes of behavior and attitude, determining which participants have similar attribute rankings in order to discover common traits among them. Each group of similar participants would then serve as the source of a persona.

Personas are not just “roles,” although they might seem to be at first. Roles are great for segmenting and grouping similar users together for analysis, but roles are not personas. Roles are defined largely by the tasks people perform, rather than by how they perform those tasks or how they feel about accomplishing the tasks. Usually, two or more personas are required to represent the range of behavior within a role.

For instance, if you are designing medical software to be used by doctors, nurses, technicians and patients, then you would want to interview people in all four roles; however, when analyzing their responses, you would compare doctors to doctors, not doctors to technicians. Their roles might overlap somewhat, but don’t muddy the water by combining data from multiple roles. Compare participants with the same role; otherwise, large differences will obscure smaller differences between participants.

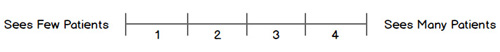

You can represent most of the observed behaviors and attitudes as a spectrum (for example, from low to high or sad to happy). Each spectrum should be discrete and divided into four levels.

In this sample spectrum, low and negative attributes are on the left, and high and positive attributes are on the right. (View large version)

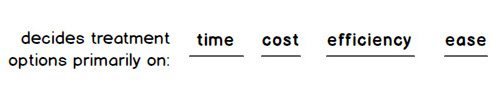

On each spectrum, participants can be given a score of 1, 2, 3 or 4 (similar to the Likert scale). The even number prevents a neutral score (for example, a score of 3 out of 5 would provide little value in creating a persona). Some variables are difficult or impossible to represent on a spectrum; in this case, don’t force it, and instead express the variable as a multiple-choice question.

To determine how many spectra to analyze, go over the responses to the interview questions and note any distinct behavior or differences in attitude. Fewer than 5 spectra is usually too few, and over 20 is too many, so aim for somewhere in between. If you have trouble deciding which spectra to use, look back at the categories of questions in the interview script shown earlier, and determine which categories most effectively group and differentiate research participants. Motivations and goals, frequency and duration of tasks, and attitudes towards tasks are good places to start.

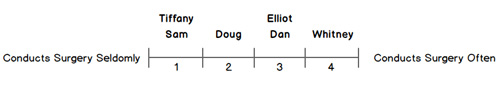

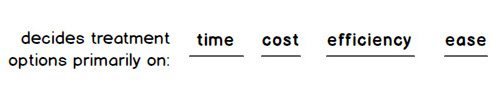

After you’ve listed 5 to 20 variables for a role, place each research participant on each spectrum, as shown below.

When placing each participant on a spectrum, keep in mind that the data is all relative at this point. The fact that Whitney does more surgeries than Doug, who does fewer than Elliot, is more important than who is a 2 rather than a 3 or 4 on the scale.

Once you’ve mapped all research participants on the spectra, it is time to identify patterns. This part might seem overwhelming, especially if you have researched many people. Start small by finding two people who tend to have the same scores on various spectra. This pattern analysis is similar to that of a semantic differential or a multivariate affinity diagram.

Of the five spectra above that describe the doctors interviewed, Tiffany and Sam appear in the same place three times, in similar places one time, and in disparate places one time. As far as we’re concerned, Tiffany and Sam are similar people and should be represented by one persona. Looking further, Dan and Elliot also have similar or the same placement on the spectra, too, but their placement differs from that of Tiffany and Sam. Dan and Elliot should be represented by a different persona from Tiffany and Sam.

This researcher has created five variables to compare the doctors who were interviewed and has mapped all of the participants to those spectra. If Tiffany and Sam tend to appear in the same or similar places in a lot of the spectra, then they probably constitute a pattern that will eventually help to describe a persona. Most of the time, the patterns that you find among participants will not apply to every single one of the spectra, because almost all patterns are imperfect.

This is not a problem; as long as participants match on a majority of the spectra, the pattern is valid. Repeat this process until you have discovered all of the patterns that represent groups of similar users. If done correctly, you will have compared a lot of the participants to each other, and the result should look something like the graph above (the color blue denotes the first pattern found).

This is where the difference between roles and personas comes into play. Even though the researcher interviewed many people who had the role of doctor, the participants had distinct patterns of responses, which will result in multiple personas with the role of doctor. Each unique pattern of behaviors and attitudes among participants should be represented by a unique persona.

6. Synthesize A Model Of Users

Now that you have groups of research participants who can be represented by different personas, decide how to describe those personas. During the interview and observation process, you might have heard responses or noticed behaviors that meaningfully characterize each research group. These common, average or dominant traits need to be captured in each persona.

7. Produce A Document For Others

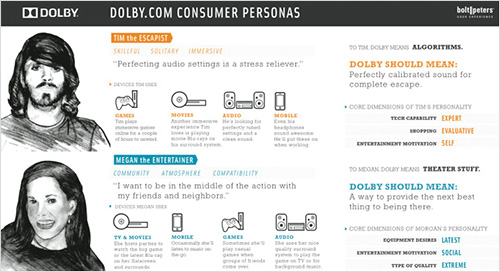

There is no one right way to create a persona document, but essential elements will need to be included. An effective persona document that communicates a model of users to others typically consists of the following:

- name,

- demographic,

- descriptive title,

- photograph,

- quote,

- a day-in-the-life narrative,

- end goals (explicit and tacit).

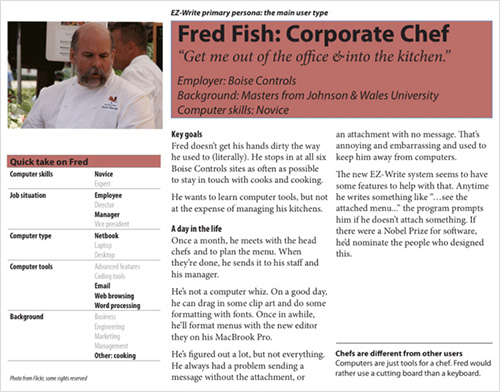

The persona document above clearly summarizes the research data. The main elements are the “Key Goals” and the “Day in the Life,” which are common to all well-made persona documents. Other elements, such as the “Quick Take on Fred” were included because of project requirements. Each project you work on will dictate a certain approach to producing persona documents.

A robust persona really only needs seven pieces to help everyone on the team understand the essentials about a user. Other elements are usually added to a document to paint an even more vivid picture, such as needs and wants, responsibilities, motivations, attitudes, pain points (i.e. problems, frustrations or road blocks), notable behavior, and design imperatives (i.e. things that a design must do to satisfy this user).

You could add a myriad of other things to a persona document, but more isn’t always better. The document is usually one page, a limitation that forces you to focus on the essential elements, without distraction or fluff. If you can’t fit everything on one page, then consider a supplemental document of some sort. Just remember that, while you’ve been immersed in the data, others will usually only see the one page. If it’s much longer, people probably won’t read it all, let alone remember the information. Keep things as brief as possible, and focus on the most salient points.

If you’re looking for a jumpstart on creating persona documents, I highly recommend the persona poster by Christof Zürn. The poster organizes and formats all of the important information that you’ll need to create an amazing one-page deliverable.

8. Socialize The Personas

By sharing the persona documents with others, you’re disseminating the knowledge that you’ve gained throughout this whole process. Consider presenting the personas to others in an engaging way, and give everyone the one-pager as a takeaway after the presentation.

The process outlined in this article is thorough and rigorous. It is based on years of refinement at Cooper and tweaked to my purposes. That being said, feel free to customize the process to fit your needs. Some parts can be simplified and even skipped after you’ve gained some experience. This is not the only way to create personas, but it is a great place to start. I hope you’ve found the process helpful.

Additional Resources

- “A Closer Look At Personas: What They Are And How They Work (Part 1),” Shlomo Goltz, Smashing Magazine The first part in this series talks about what personas are and why they are so effective in the creative process.

- “Understanding Your Users: Developing Personas” (slidedeck), Shlomo Goltz Use these presentation slides to kick off a persona creation project.

- “Provisional Personas: Workshop” (slidedeck), Shlomo Goltz This guide walks through the process of creating provisional personas.

- “The Persona Core Poster: A Service Design Tool,” Christof Zürn This template can be used to create a one-page deliverable.

Further Reading

- A Closer Look At Personas (Part 1)

- Designing For The Multifaceted User

- Better User Experience With Storytelling

- Getting Back Into The (Right) Deliverables Business

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers