Making A Service Worker: A Case Study

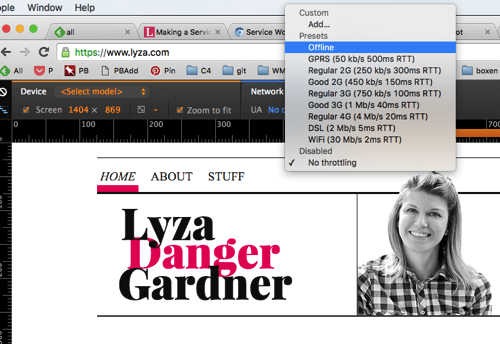

There’s no shortage of boosterism or excitement about the fledgling service worker API, now shipping in some popular browsers. There are cookbooks and blog posts, code snippets and tools. But I find that when I want to learn a new web concept thoroughly, rolling up my proverbial sleeves, diving in and building something from scratch is often ideal.

The bumps and bruises, gotchas and bugs I ran into this time have benefits: Now I understand service workers a lot better, and with any luck I can help you avoid some of the headaches I encountered when working with the new API.

Service workers do a lot of different things; there are myriad ways to harness their powers. I decided to build a simple service worker for my (static, uncomplicated) website that roughly mirrors the features that the obsolete Application Cache API used to provide — that is:

- make the website function offline,

- increase online performance by reducing network requests for certain assets,

- provide a customized offline fallback experience.

Before beginning, I’d like to acknowledge two people whose work made this possible. First, I’m hugely indebted to Jeremy Keith for the implementation of service workers on his own website, which served as the starting point for my own code. I was inspired by his recent post describing his ongoing service worker experiences. In fact, my work is so heavily derivative that I wouldn’t have written about it except for Jeremy’s exhortation in an earlier post:

"So if you decide to play around with Service Workers, please, please share your experience."

Secondly, all sorts of big old thanks to Jake Archibald for his excellent technical review and feedback. Always nice when one of the service worker specification’s creators and evangelists is able to set you straight!

What Is A Service Worker?

A service worker is a script that stands between your website and the network, giving you, among other things, the ability to intercept network requests and respond to them in different ways.

In order for your website or app to work, the browser fetches its assets — such as HTML pages, JavaScript, images, fonts. In the past, the management of this was chiefly the browser’s prerogative. If the browser couldn’t access the network, you would probably see its “Hey, you’re offline” message. There were techniques you could use to encourage the local caching of assets, but the browser often had the last say.

This wasn’t such a great experience for users who were offline, and it left web developers with little control over browser caching.

Cue Application Cache (or AppCache), whose arrival several years ago seemed promising. It ostensibly let you dictate how different assets should be handled, so that your website or app could work offline. Yet AppCache’s simple-looking syntax belied its underlying confounding nature and lack of flexibility.

The fledgling service worker API can do what AppCache did, and a whole lot more. But it looks a little daunting at first. The specifications make for heavy and abstract reading, and numerous APIs are subservient to it or otherwise related: cache, fetch, etc. Service workers encompass so much functionality: push notifications and, soon, background syncing. Compared to AppCache, it looks… complicated.

Whereas AppCache (which, by the way, is going away) was easy to learn but terrible for every single moment after that (my opinion), service workers are more of an initial cognitive investment, but they are powerful and useful, and you can generally get yourself out of trouble if you break things.

Some Basic Service Worker Concepts

A service worker is a file with some JavaScript in it. In that file you can write JavaScript as you know and love it, with a few important things to keep in mind.

Service worker scripts run in a separate thread in the browser from the pages they control. There are ways to communicate between workers and pages, but they execute in a separate scope. That means you won’t have access to the DOM of those pages, for example. I visualize a service worker as sort of running in a separate tab from the page it affects; this is not at all accurate, but it is a helpful rough metaphor for keeping myself out of confusion.

JavaScript in a service worker must not block. You need to use asynchronous APIs. For example, you cannot use localStorage in a service worker (localStorage is a synchronous API). Humorously enough, even knowing this, I managed to run the risk of violating it, as we’ll see.

Registering A Service Worker

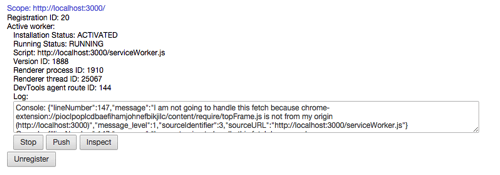

You make a service worker take effect by registering it. This registration is done from outside the service worker, by another page or script on your website. On my website, a global site.js script is included on every HTML page. I register my service worker from there.

When you register a service worker, you (optionally) also tell it what scope it should apply itself to. You can instruct a service worker only to handle stuff for part of your website (for example, ’/blog/’) or you can register it for your whole website (’/’) like I do.

Service Worker Lifecycle And Events

A service worker does the bulk of its work by listening for relevant events and responding to them in useful ways. Different events are triggered at different points in a service worker’s lifecycle.

Once the service worker has been registered and downloaded, it gets installed in the background. Your service worker can listen for the install event and perform tasks appropriate for this stage.

In our case, we want to take advantage of the install state to pre-cache a bunch of assets that we know we will want available offline later.

After the install stage is finished, the service worker is then activated. That means the service worker is now in control of things within its scope and can do its thing. The activate event isn’t too exciting for a new service worker, but we’ll see how it’s useful when updating a service worker with a new version.

Exactly when activation occurs depends on whether this is a brand new service worker or an updated version of a pre-existing service worker. If the browser does not have a previous version of a given service worker already registered, activation will happen immediately after installation is complete.

Once installation and activation are complete, they won’t occur again until an updated version of the service worker is downloaded and registered.

Beyond installation and activation, we’ll be looking primarily at the fetch event today to make our service worker useful. But there are several useful events beyond that: sync events and notification events, for example.

For extra credit or leisure fun, you can read more about the interfaces that service workers implement. It’s by implementing these interfaces that service workers get the bulk of their events and much of their extended functionality.

The Service Worker’s Promise-Based API

The service worker API makes heavy use of Promises. A promise represents the eventual result of an asynchronous operation, even if the actual value won’t be known until the operation completes some time in the future.

getAnAnswerToADifficultQuestionSomewhereFarAway()

.then(answer => {

console.log('I got the ${answer}!');

})

.catch(reason => {

console.log('I tried to figure it out but couldn't because ${reason}');

});

The getAnAnswer… function returns a Promise that (we hope) will eventually be fulfilled by, or resolve to, the answer we’re looking for. Then, that answer can be fed to any chained then handler functions, or, in the sorry case of failure to achieve its objective, the Promise can be rejected — often with a reason — and catch handler functions can take care of these situations.

There’s more to promises, but I’ll try to keep the examples here straightforward (or at least commented). I urge you to do some informative reading if you’re new to promises.

Note: I use certain ECMAScript6 (or ES2015) features in the sample code for service workers because browsers that support service workers also support these features. Specifically here, I am using arrow functions and template strings.

Other Service Worker Necessities

Also, note that service workers require HTTPS to work. There is an important and useful exception to this rule: Service workers work for localhost on insecure http, which is a relief because setting up local SSL is sometimes a slog.

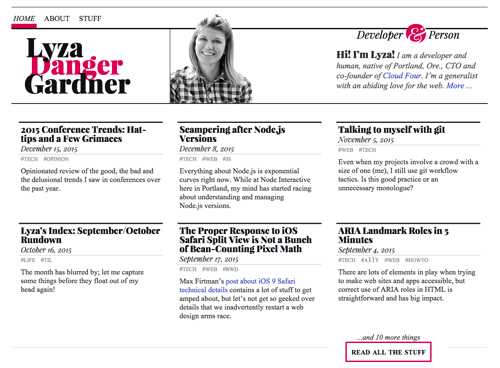

Fun fact: This project forced me to do something I’d been putting off for a while: getting and configuring SSL for the www subdomain of my website. This is something I urge folks to consider doing because pretty much all of the fun new stuff hitting the browser in the future will require SSL to be used.

All of the stuff we’ll put together works today in Chrome (I use version 47). Any day now, Firefox 44 will ship, and it supports service workers. Is Service Worker Ready? provides granular information about support in different browsers.

Registering, Installing And Activating A Service Worker

Now that we’ve taken care of some theory, we can start putting together our service worker.

To install and activate our service worker, we want to listen for install and activate events and act on them.

We can start with an empty file for our service worker and add a couple of eventListeners. In serviceWorker.js:

self.addEventListener('install', event => {

// Do install stuff

});

self.addEventListener('activate', event => {

// Do activate stuff: This will come later on.

});Registering Our Service Worker

Now we need to tell the pages on our website to use the service worker.

Remember, this registration happens from outside the service worker — in my case, from within a script (/js/site.js) that is included on every page of my website.

In my site.js:

if ('serviceWorker' in navigator) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/serviceWorker.js', {

scope: '/'

});

}Pre-Caching Static Assets During Install

I want to use the install stage to pre-cache some assets on my website.

- By pre-caching some static assets (images, CSS, JavaScript) that are used by many pages on my website, I can speed up loading times by grabbing these out of cache, instead of fetching from the network on subsequent page loads.

- By pre-caching an offline fallback page, I can show a nice page when I can’t fulfill a page request because the user is offline.

The steps to do this are:

- Tell the

installevent to hang on and not to complete until I’ve done what I need to do by usingevent.waitUntil. - Open the appropriate

cache, and stick the static assets in it by usingCache.addAll. In progressive web app parlance, these assets make up my “application shell.”

In /serviceWorker.js, let’s expand the install handler:

self.addEventListener('install', event => {

function onInstall () {

return caches.open('static')

.then(cache => cache.addAll([

'/images/lyza.gif',

'/js/site.js',

'/css/styles.css',

'/offline/',

'/'

])

);

}

event.waitUntil(onInstall(event));

});The service worker implements the CacheStorage interface, which makes the caches property available globally in our service worker. There are several useful methods on caches — for example, open and delete.

You can see Promises at work here: caches.open returns a Promise resolving to a cache object once it has successfully opened the static cache; addAll also returns a Promise that resolves when all of the items passed to it have been stashed in the cache.

I tell the event to wait until the Promise returned by my handler function is resolved successfully. Then we can be sure that all of those pre-cache items get sorted before the installation is complete.

Console Confusions

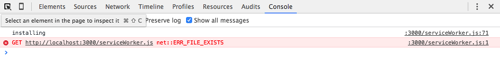

Stale Logging

Possibly not a bug, but certainly a confusion: If you console.log from service workers, Chrome will continue to re-display (rather than clear) those log messages on subsequent page requests. This can make it seem like events are firing too many times or like code is executing over and over.

For example, let’s add a log statement to our install handler:

self.addEventListener('install', event => {

// … as before

console.log('installing');

});

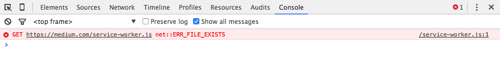

install event on every page load. Instead, it’s showing stale logs. (View large version)An Error When Things Are OK

Another odd thing is that once a service worker is installed and activated, subsequent page loads for any page within its scope will always cause a single error in the console. I thought I was doing something wrong.

What We’ve Accomplished So Far

The service worker handles the install event and pre-caches some static assets. If you were to use this service worker and register it, it would indeed pre-cache the indicated assets but wouldn’t yet be able to take advantage of them offline.

The contents of serviceWorker.js are on GitHub.

Fetch Handling With Service Workers

So far, our service worker has a fleshed-out install handler but doesn’t do anything beyond that. The magic of our service worker is really going to happen when fetch events are triggered.

We can respond to fetches in different ways. By using different network strategies, we can tell the browser to always try to fetch certain assets from the network (making sure key content is fresh), while favoring cached copies for static assets — really slimming down our page payloads. We can also provide a nice offline fallback if all else fails.

Whenever a browser wants to fetch an asset that is within the scope of this service worker, we can hear about it by, yep, adding an eventListener in serviceWorker.js:

self.addEventListener('fetch', event => {

// … Perhaps respond to this fetch in a useful way?

});

Again, every fetch that falls within this service worker’s scope (i.e. path) will trigger this event — HTML pages, scripts, images, CSS, you name it. We can selectively handle the way the browser responds to any of these fetches.

Should We Handle This Fetch?

When a fetch event occurs for an asset, the first thing I want to determine is whether this service worker should interfere with the fetching of the given resource. Otherwise, it should do nothing and let the browser assert its default behavior.

We’ll end up with basic logic like this in serviceWorker.js:

self.addEventListener('fetch', event => {

function shouldHandleFetch (event, opts) {

// Should we handle this fetch?

}

function onFetch (event, opts) {

// … TBD: Respond to the fetch

}

if (shouldHandleFetch(event, config)) {

onFetch(event, config);

}

});The shouldHandleFetch function assesses a given request to determine whether we should provide a response or let the browser assert its default handling.

Why Not Use Promises?

To keep with service worker’s predilection for promises, the first version of my fetch event handler looked like this:

self.addEventListener('fetch', event => {

function shouldHandleFetch (event, opts) { }

function onFetch (event, opts) { }

shouldHandleFetch(event, config)

.then(onFetch(event, config))

.catch(…);

});Seems logical, but I was making a couple of rookie mistakes with promises. I swear I did sense a code smell even initially, but it was Jake who set me straight on the errors of my ways. (Lesson: As always, if code feels wrong, it probably is.)

Promise rejections should not be used to indicate, “I got an answer I didn’t like.” Instead, rejections should indicate, “Ah, crap, something went wrong in trying to get the answer.” That is, rejections should be exceptional.

Criteria For Valid Requests

Right, back to determining whether a given fetch request is applicable for my service worker. My site-specific criteria are as follows:

- The requested URL should represent something I want to cache or respond to. Its path should match a

Regular Expressionof valid paths. - The request’s HTTP method should be

GET. - The request should be for a resource from my origin (

lyza.com).

If any of the criteria tests evaluate to false, we should not handle this request. In serviceWorker.js:

function shouldHandleFetch (event, opts) {

var request = event.request;

var url = new URL(request.url);

var criteria = {

matchesPathPattern: !!(opts.cachePathPattern.exec(url.pathname),

isGETRequest : request.method === 'GET',

isFromMyOrigin : url.origin === self.location.origin

};

// Create a new array with just the keys from criteria that have

// failing (i.e. false) values.

var failingCriteria = Object.keys(criteria)

.filter(criteriaKey => !criteria[criteriaKey]);

// If that failing array has any length, one or more tests failed.

return !failingCriteria.length;

}Of course, the criteria here are my own and would vary from site to site. event.request is a Request object that has all kinds of data you can look at to assess how you’d like your fetch handler to behave.

Trivial note: If you noticed the incursion of config, passed as opts to handler functions, well spotted. I factored out some reusable config-like values and created a config object in the top-level scope of the service worker:

var config = {

staticCacheItems: [

'/images/lyza.gif',

'/css/styles.css',

'/js/site.js',

'/offline/',

'/'

],

cachePathPattern: /^\/(?:(20[0-9]{2}|about|blog|css|images|js)\/(.+)?)?$/

};

Why Whitelist?

You may be wondering why I’m only caching things with paths that match this regular expression:

/^/(?:(20[0-9]{2}|about|blog|css|images|js)/(.+)?)?$/

… instead of caching anything coming from my own origin. A couple of reasons:

- I don’t want to cache the service worker itself.

- When I’m developing my website locally, some requests generated are for things I don’t want to cache. For example, I use

browserSync, which kicks off a bunch of related requests in my development environment. I don’t want to cache that stuff! It seemed messy and challenging to try to think of everything I wouldn’t want to cache (not to mention, a little weird to have to spell it out in my service worker’s configuration). So, a whitelist approach seemed more natural.

Writing The Fetch Handler

Now we’re ready to pass applicable fetch requests on to a handler. The onFetch function needs to determine:

- what kind of resource is being requested,

- and how I should fulfill this request.

1. What Kind Of Resource Is Being Requested?

I can look at the HTTP Accept header to get a hint about what kind of asset is being requested. This helps me figure out how I want to handle it.

function onFetch (event, opts) {

var request = event.request;

var acceptHeader = request.headers.get('Accept');

var resourceType = 'static';

var cacheKey;

if (acceptHeader.indexOf('text/html') !== -1) {

resourceType = 'content';

} else if (acceptHeader.indexOf('image') !== -1) {

resourceType = 'image';

}

// {String} [static|image|content]

cacheKey = resourceType;

// … now do something

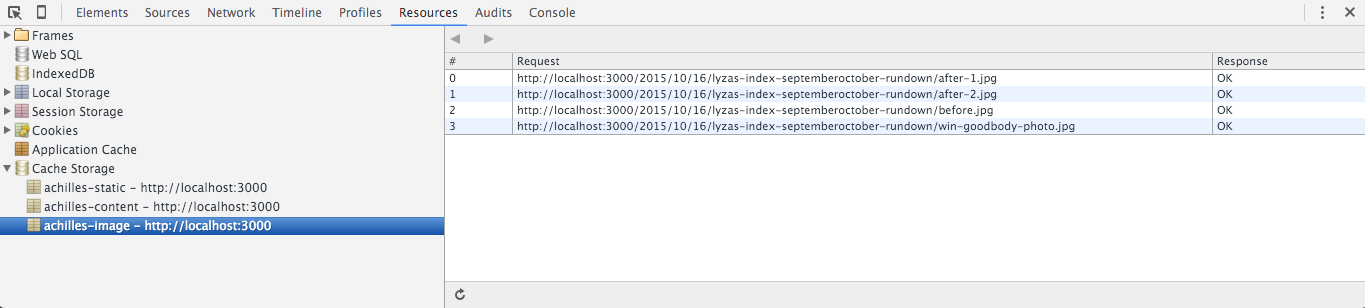

}To stay organized, I want to stick different kinds of resources into different caches. This will allow me to manage those caches later. These cache key Strings are arbitrary — you can call your caches whatever you’d like; the cache API doesn’t have opinions.

2. Respond To The Fetch

The next thing for onFetch to do is to respondTo the fetch event with an intelligent Response.

function onFetch (event, opts) {

// 1. Determine what kind of asset this is… (above).

if (resourceType === 'content') {

// Use a network-first strategy.

event.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => fetchFromCache(event))

.catch(() => offlineResponse(opts))

);

} else {

// Use a cache-first strategy.

event.respondWith(

fetchFromCache(event)

.catch(() => fetch(request))

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => offlineResponse(resourceType, opts))

);

}

}Careful With Async!

In our case, shouldHandleFetch doesn’t do anything asynchronous, and neither does onFetch up to the point of event.respondWith. If something asynchronous had happened before that, we would be in trouble. event.respondWith must be called between the fetch event firing and control returning to the browser. Same goes for event.waitUntil. Basically, if you’re handling an event, either do something immediately (synchronously) or tell the browser to hang on until your asynchronous stuff is done.

HTML Content: Implementing A Network-First Strategy

Responding to fetch requests involves implementing an appropriate network strategy. Let’s look more closely at the way we’re responding to requests for HTML content (resourceType === ‘content’).

if (resourceType === 'content') {

// Respond with a network-first strategy.

event.respondWith(

fetch(request)

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => fetchFromCache(event))

.catch(() => offlineResponse(opts))

);

}The way we fulfill requests for content here is a network-first strategy. Because HTML content is the core concern of my website and it changes often, I always try to get fresh HTML documents from the network.

Let’s step through this.

1. Try Fetching From The Network

fetch(request)

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

If the network request is successful (i.e. the promise resolves), go ahead and stash a copy of the HTML document in the appropriate cache (content). This is called read-through caching:

function addToCache (cacheKey, request, response) {

if (response.ok) {

var copy = response.clone();

caches.open(cacheKey).then( cache => {

cache.put(request, copy);

});

return response;

}

}Responses may be used only once.

We need to do two things with the response we have:

- cache it,

- respond to the event with it (i.e. return it).

But Response objects may be used only once. By cloning it, we are able to create a copy for the cache’s use:

var copy = response.clone();

Don’t cache bad responses. Don’t make the same mistake I did. The first version of my code didn’t have this conditional:

if (response.ok)Pretty awesome to end up with 404 or other bad responses in the cache! Only cache happy responses.

2. Try To Retrieve From Cache

If retrieving the asset from the network succeeds, we’re done. However, if it doesn’t, we might be offline or otherwise network-compromised. Try retrieving a previously cached copy of the HTML from cache:

fetch(request)

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => fetchFromCache(event))

Here is the fetchFromCache function:

function fetchFromCache (event) {

return caches.match(event.request).then(response => {

if (!response) {

// A synchronous error that will kick off the catch handler

throw Error('${event.request.url} not found in cache');

}

return response;

});

}Note: Don’t indicate which cache you wish to check with caches.match; check ’em all at once.

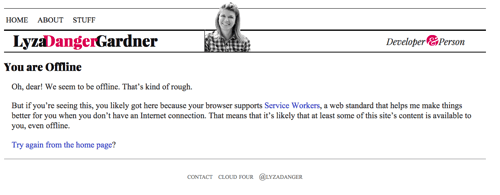

3. Provide An Offline Fallback

If we’ve made it this far but there’s nothing in the cache we can respond with, return an appropriate offline fallback, if possible. For HTML pages, this is the page cached from /offline/. It’s a reasonably well-formatted page that tells the user they’re offline and that we can’t fulfill what they’re after.

fetch(request)

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => fetchFromCache(event))

.catch(() => offlineResponse(opts))

And here is the offlineResponse function:

function offlineResponse (resourceType, opts) {

if (resourceType === 'image') {

return new Response(opts.offlineImage,

{ headers: { 'Content-Type': 'image/svg+xml' } }

);

} else if (resourceType === 'content') {

return caches.match(opts.offlinePage);

}

return undefined;

}

Other Resources: Implementing A Cache-First Strategy

The fetch logic for resources other than HTML content uses a cache-first strategy. Images and other static content on the website rarely change; so, check the cache first and avoid the network roundtrip.

event.respondWith(

fetchFromCache(event)

.catch(() => fetch(request))

.then(response => addToCache(cacheKey, request, response))

.catch(() => offlineResponse(resourceType, opts))

);

The steps here are:

- try to retrieve the asset from cache;

- if that fails, try retrieving from the network (with read-through caching);

- if that fails, provide an offline fallback resource, if possible.

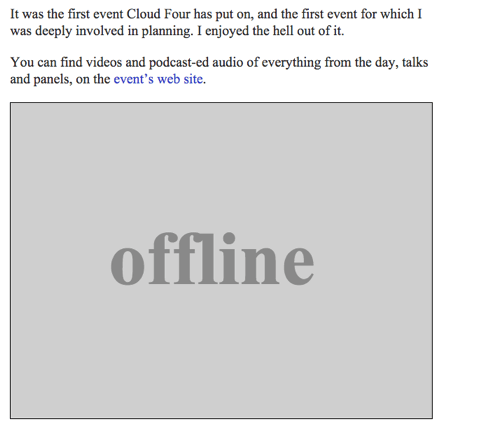

Offline Image

We can return an SVG image with the text “Offline” as an offline fallback by completing the offlineResource function:

function offlineResponse (resourceType, opts) {

if (resourceType === 'image') {

// … return an offline image

} else if (resourceType === 'content') {

return caches.match('/offline/');

}

return undefined;

}And let’s make the relevant updates to config:

var config = {

// …

offlineImage: '<svg role="img" aria-labelledby="offline-title"'

+ 'viewBox="0 0 400 300" xmlns="https://www.w3.org/2000/svg">'

+ '<title id="offline-title">Offline</title>'

+ '<g fill="none" fill-rule="evenodd"><path fill=>"#D8D8D8" d="M0 0h400v300H0z"/>'

+ '<text fill="#9B9B9B" font-family="Times New Roman,Times,serif" font-size="72" font-weight="bold">'

+ '<tspan x="93" y="172">offline</tspan></text></g></svg>',

offlinePage: '/offline/'

};

Watch Out For CDNs

Watch out for CDNs if you are restricting fetch handling to your origin. When constructing my first service worker, I forgot that my hosting provider sharded assets (images and scripts) onto its CDN, so that they no were no longer served from my website’s origin (lyza.com). Whoops! That didn’t work. I ended up disabling the CDN for the affected assets (but optimizing those assets, of course!).

Completing The First Version

The first version of our service worker is now done. We have an install handler and a fleshed-out fetch handler that can respond to applicable fetches with optimized responses, as well as provide cached resources and an offline page when offline.

As users browse the website, they’ll continue to build up more cached items. When offline, they’ll be able to continue to browse items they’ve already got cached, or they’ll see an offline page (or image) if the resource requested isn’t available in cache.

The full code with fetch handling (serviceWorker.js) is on GitHub.

Versioning And Updating The Service Worker

If nothing were ever going to change on our website again, we could say we’re done. However, service workers need to be updated from time to time. Maybe I’ll want to add more cache-able paths. Maybe I want to evolve the way my offline fallbacks work. Maybe there’s something slightly buggy in my service worker that I want to fix.

I want to stress that there are automated tools for making service-worker management part of your workflow, like Service Worker Precache from Google. You don’t need to manage versioning this by hand. However, the complexity on my website is low enough that I use a human versioning strategy to manage changes to my service worker. This consists of:

- a simple version string to indicate versions,

- implementation of an

activatehandler to clean up after old versions, - updating of the

installhandler to make updated service workersactivatefaster.

Versioning Cache Keys

I can add a version property to my config object:

version: 'aether'This should change any time I want to deploy an updated version of my service worker. I use the names of Greek deities because they’re more interesting to me than random strings or numbers.

Note: I made some changes to the code, adding a convenience function (cacheName) to generate prefixed cache keys. It’s tangential, so I’m not including it here, but you can see it in the completed service worker code.

achilles.) (View large version)Don’t Rename Your Service Worker

At one point, I was futzing around with naming conventions for the service worker’s file name. Don’t do this. If you do, the browser will register the new service worker, but the old service worker will stay installed, too. This is a messy state of affairs. I’m sure there’s a workaround, but I’d say don’t rename your service worker.

Don’t Use importScripts For config

I went down a path of putting my config object in an external file and using self.importScripts() in the service worker file to pull that script in. That seemed like a reasonable way to manage my config outside of the service worker, but there was a hitch.

The browser byte-compares service worker files to determine whether they have been updated — that’s how it knows when to re-trigger a download-and-install cycle. Changes to the external config don’t cause any changes to the service worker itself, meaning that changes to the config weren’t causing the service worker to update. Whoops.

Adding An Activate Handler

The purpose of having version-specific cache names is so that we can clean up caches from previous versions. If there are caches around during activation that are not prefixed with the current version string, we’ll know that they should be deleted because they are crufty.

Cleaning Up Old Caches

We can use a function to clean up after old caches:

function onActivate (event, opts) {

return caches.keys()

.then(cacheKeys => {

var oldCacheKeys = cacheKeys.filter(key =>

key.indexOf(opts.version) !== 0

);

var deletePromises = oldCacheKeys.map(oldKey => caches.delete(oldKey));

return Promise.all(deletePromises);

});

}Speeding Up Install And Activate

An updated service worker will get downloaded and will install in the background. It is now a worker in waiting. By default, the updated service worker will not activate while any pages are loaded that are still using the old service worker. However, we can speed that up by making a small change to our install handler:

self.addEventListener('install', event => {

// … as before

event.waitUntil(

onInstall(event, config)

.then( () => self.skipWaiting() )

);

});skipWaiting will cause activate to happen immediately.

Now, finish the activate handler:

self.addEventListener('activate', event => {

function onActivate (event, opts) {

// … as above

}

event.waitUntil(

onActivate(event, config)

.then( () => self.clients.claim() )

);

});self.clients.claim will make the new service worker take effect immediately on any open pages in its scope.

chrome://serviceworker-internals in Chrome to see all of the service workers that the browser has registered. (View large version)

Ta-Da!

We now have a version-managed service worker! You can see the updated serviceWorker.js file with version management on GitHub.

Further Reading

- A Beginner’s Guide To Progressive Web Apps

- Building A Simple Cross-Browser Offline To-Do List

- World Wide Web, Not Wealthy Western Web

- Getting Started With Neon Branching

Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

Register Free Now

Register Free Now