The Value Of Concept Testing As Part Of Product Design

UX design teams are passionate about our approach to solving problems and providing users with experiences that lead to their desired outcomes. Without some type of user input guiding our process, we are left being directed by the same high-level stakeholder assumptions we often rally against as being the antithesis to UX: those holding the purse strings have the loudest voice in the room.

Concept testing is a research method that involves getting user feedback during the upfront part of the design process to give feedback on potential solutions. Concept testing at the beginning phase of product development allows users to share in the initial shaping of an idea to solve a problem.

For example, let’s say a large bank wants to make it easier for customers to enroll in direct deposit, you would be fairly safe to assume that allowing customers to complete the enrollment process online from start to finish would be an easy win to solve this problem. However, with limited resources including time, money, and available labor, decisions need to be made:

"Should the enrollment be mobile friendly? Can/should enrollment happen in a native app and online? Should banks have computer kiosks set up for in-person customers to enroll? How aligned are customers’ goals with the goals of the business as it relates to the idea of enrolling in direct deposit?"

These are only a few questions of many that you can immediately come up with based on the concept of enrolling in direct deposit online — a relatively simple idea.

Concept testing allows you to reduce risk while increasing focus on user input on building out a product to meet user needs. Concept testing does not take the place of being visionary, however, being visionary without insight from others might be analogous to throwing spaghetti at a moving target and getting lucky every now and then — concept testing will help slow down that target or increase your spaghetti-throwing accuracy.

What Is Concept Testing?

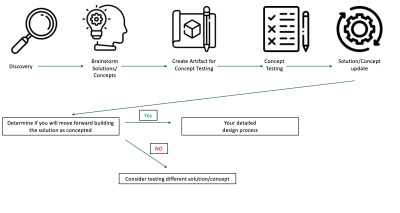

Concept testing, as I’m describing in this article, is the process of getting feedback from stakeholders and users on a solution that has yet to come to life through detailed design. Concept testing as I’m describing here is a hybrid of market research and UX research in that we are examining if the idea or solution has a potential market and if it does, just how we might best execute delivering the experience.

I believe concept testing is a pivotal part of the up-front UX process. UX teams should consider it a mandatory step in designing a product. We sometimes run into projects where the upfront discovery with users is rushed or overlooked as unnecessary. Concept testing allows you to justify engaging or re-engaging with users before building out the product in a detailed design.

For example, if you are hired at Big Bank X and they want to build a new financial service they can offer online, they might have already completely defined the service from the business perspective and expect detailed design to commence immediately (not a UX approach, but one that is often followed by large businesses). Your UX team can ask for some space to get the general concept in front of users by saying concept testing is a standard part of any request for work you accept. You can take the argument from there; I’m aware these things don’t always end the ideal way.

Concept testing allows you to validate an idea before you invest resources in building something that misses the mark. You’ll identify potential roadblocks to implementing your idea that you may have missed if you ask the right questions during testing. Concept testing does not serve as a replacement for usability testing when you have more refined design wireframes or prototypes with detailed design.

Concept testing is a great next step once you’ve done basic discovery work identifying the problem and building empathy with users through user research. You might hold workshops or working sessions with key stakeholders and users as the idea is grown from a seed in order to generate the artifacts we will discuss below, but I suggest waiting to build out the requirements of the product until you’ve done testing.

There is such a thing as too early to concept test. If you have a complex idea or one that is too abstract to be relatable I suggest doing a little more work to refine the use cases and realistic scenarios in which you might present users with the product. If you haven’t reached a critical mass of which testing is a valuable use of the resources required, you should hold off until the concept becomes more thought out or you have additional concepts to include in testing to make it worthwhile.

You can test concepts in a number of ways, I’ll cover a few in this article, but each way includes getting feedback from potential end-users on the validity and execution of the idea. You can engage in concept testing as part of an interview with a participant in which they provide feedback on the concept. You might execute concept testing in person, remote, asynchronous-unmoderated depending on your goals and testing artifacts. I’ll discuss this all in detail, but first I want to cover the importance of testing.

Explore Novel Ideas To Beyond What Your Team Already Has

Concept testing can help you identify a viable idea for the present and also identify ideas you might implement in the future when technology or society is ready. For example, you might add an aspect of augmented reality to your concept testing and get some ideas around the expectations and challenges for implementation while knowing this isn’t the main focus or immediate outcome of the concept testing. You can explore ideas that are out of your typical comfort zone without giving the impression you will create the product or invest in resources to build a more authentic experience to test.

Who To Involve In Concept Testing?

You should involve as many members of the product team as possible in concept testing. Your full design team should be a part of creating and executing concept testing. You’ll need researchers to actively engage in creating the protocol, designers to help with any relevant artifacts, information architects and content strategists to help apply their knowledge as needed and to learn from the findings.

The value in concept testing extends beyond UX and you should include members beyond the UX team in the process of carrying out testing. This includes:

- Marketing team members,

- Tech/Dev team members,

- Business analysts,

- Key internal stakeholders from outside the core product team.

You can invite these team members to join planning sessions or leave it as simple as inviting them to view a testing session so they see how users respond to the idea. I’ll caution that sometimes only viewing one testing session (or one research session) will leave a key stakeholder with an impression based on what was discussed during that session, and it might make it more difficult to convey conflicting information from other sessions if that stakeholder has formed a full opinion based on what they saw with their own eyes.

Another tactic for getting key stakeholder buy-in is to have them be participants in the testing sessions. You can mix in key stakeholders who might also be users or work closely with users (for example, supervisors at an HR service provider call center might be good to include as part of the participants to test the concept of your new idea for a virtual assistant tool call center reps would use while servicing calls, along with using actual call center reps who might benefit from using the tool daily). This allows key stakeholders to gain an understanding of the concept and potentially become advocates of the idea coming to fruition. However, you should not focus solely on internal stakeholders as a concept testing population.

Representative end-users should ultimately have a large say in how a concept evolves if we are practicing what we preach as UX practitioners. That doesn’t mean you can only move forward with ideas that users suggest are great ideas. What it might mean is:

- You might want to make tweaks to parts of the idea that didn’t test well before moving forward.

- You haven’t identified the correct audience for your concept and you need to expand or redefine the user base.

- The idea itself isn’t easily understood and you need to explore what you can do to make it easier to understand.

- It could mean the problem being solved isn’t well understood and you’ll need to be patient upfront while adoption occurs and users realize the extent of the need for the solution.

What Artifacts Can You Use In Testing?

Effective concept testing requires some type of artifact to convey the idea. I’ve changed my opinion on this as I’ve grown as a researcher. I initially thought it was a better idea to test concepts completely in the abstract — as a researcher, I wanted to avoid leading people. But in reality, people can become frustrated or make guesses that aren’t helpful when they are simply presented with the question — what do you think of when I say “financial command center?” Instead, showing them a simple sketch of some charts representing the concept of personal financial data being monitored can generate a robust conversation where they provide deep insight into the direction and critical functionality of a “financial command center.”

Although I changed my thinking and now believe artifacts are key to concept testing, I do think it’s important to keep it conceptual — the point is to present ideas and let users expand on them, not grab users tightly by the hand and walk them to the conclusion that your idea is great and usable. The purpose of the artifact is to ground the research participant’s thinking in the reality the future concept would exist and allow them to think about how the concept would apply to this reality.

You can be creative, but here are some potential artifacts you can use in concept testing:

- Sketches and drawings

Many concepts for both physical and digital products start as sketches. You can take something as simple as a few sketched-out screens or a comic strip laying out an interaction in a way that might convey the concept. You might be creative in how finished or unfinished the sketches are and ask your testing participants to finalize the sketches or move into the next frame of a story with what they expect would happen next. - Craft supplies

You can use tangible, tactile artifacts to help convey a concept. In one of my case studies, I’ll share how we used velcro and felt to have potential users explore the concept of a touch screen kiosk at a zoo exhibit. I’ve also been a part of studies where we created an ATM out of cardboard to simulate a user interacting with an ATM as part of the concept. These types of artifacts allow you a low expense, low fidelity way to convey higher expense, higher fidelity ideas. - Sticky notes

You can use sticky notes to indicate a workflow, with each step placed on a different sticky note. You might allow interview participants to reorder and add to the sticky notes in order to design their ideal solution based on the seed of the concept you’ve provided.

- Let participants create something.

You might want to have users take the concept from an idea you share into what they would create if they were executing the idea. This would allow you to explore the features, functionalities, and imagined use cases potential users have while they build out an experience they believe would either meet their needs or align with their understanding of how they might use the concept. I suggest doing this as a group activity; a researcher can facilitate a discussion while participants create and explain their solutions. You can use either paper and pencils for users to sketch out the idea or craft supplies to have them create something. Give participants a warm-up activity such as how to make toast, then have them solve for the topic you are solving for. The idea is to understand the logic behind what participants feel the ideal solution might be, designers can then translate those requirements into a digital context and use them as inspiration.

I don’t think this is an exhaustive list of the types of artifacts you can use. I encourage you to be creative and really allow for users to be the ones who take the artifact and turn the concept into an experience that is useful for them.

Two Common Concept Testing Methods: Interviews And A/B Testing

Interviews

We often use interviews combined with artifacts in UX research. A concept testing interview focuses on the concept and covers the high-level areas of:

- Hypothesis testing

Questions to explore the supposed need the concept will address. Do users really struggle with accomplishing a task or have an unmet need in the area your concept will provide a solution? Will this concept meet the needs the users have? - How potential users are currently solving the problem

What are the use cases for your concept? How are users meeting their needs currently? Is this a manual process you might automate? Is this something that is being done outside of your system that you’d like to integrate through features? Is this something users aren’t aware they are doing that’s additional, but you’ve identified a technology that could remove a step from their process? - Current comparative/competitive products

What other tools or systems are users using to meet their needs? What types of experiences do users think might be relevant to the concept you’re exploring? - Value proposition

You can explore what makes your product valuable when understanding how it addresses the pain points they share. You can use the data from the previous two bullets to help inform the way your product can differentiate itself from current solutions. How do users talk about the value of your concept? You can use these words in future marketing of your product to convey the value proposition. - Use of the artifact to elicit feedback

Get direct feedback on the artifact you’ve created or are having users create.

You can conduct these types of interviews remotely, however it might be difficult if you have a tangible artifact or want someone to build on your concept using craft material. I’d recommend using an online whiteboard or collaboration tool to accomplish remote co-create. Canvas Chrome, Google Jamboard, Miro, and Mural, are four examples of many online collaboration spaces that exist to serve the needs of remote co-creation.

A/B Testing Using Artifacts

Do you have multiple ideas around how to best bring your concept to life? If you are at a decision-making point, say you want to determine if mobile or desktop is the right way to focus your initial effort, you can introduce multiple artifacts to compare multiple versions of your idea. You can answer each of the questions listed in the interview section of this article, and additionally, A/B testing will allow you to determine:

- Which version of your concept conveys your idea clearer?

- Which version of your concept provides a more immediate value?

- Which version of your concept is more realistic to bring to life and meet users’ needs?

A/B testing requires greater resources in terms of creating an artifact to test. You’ll need at least two versions of an idea to move forward with A/B testing. You can conduct A/B testing asynchronously, having users log into a site hosting visualizations of the concept and asking them questions along the way. This might be static such as having the user view the concept then respond to questions, or it can be similar to how UserZoom or Usabilitytesting.com present questions in the context of a participant walking through a site or prototype. Many of these platforms for gathering user feedback also allow you to have users give audio responses or provide feedback on the overall experience upon the conclusion of their session.

Asynchronous unmoderated A/B concept testing can allow you to include a larger number of participants without requiring you to dedicate time to conducting each session. You might have your testing split so that participants only encounter the A or the B version of the concept, or you might have them view both and leave feedback comparing the two, as well as including metrics answering the questions in the bullets above.

Other potential methods

Co-design allows users to continue building out an idea you have. You might not want to introduce an artifact upfront in codesign, that way you aren’t biasing what participants might create. You can work with the designers to help create prompts for activities to facilitate participants in designing a solution to an existing problem using the materials you provide. This can be sketching, clay, pipe cleaners, and other crafting supplies, or it can be words you capture from participants describing a solution or what they would imagine a product that meets their needs could be. You can then use these creations/descriptions to align your idea or validate that your idea aligns with how users imagine their needs might be met. You might use an online whiteboard space (again, Miro, Mural, and many others are available) to cocreate virtually if participants are all remote.

Survey allows broader feedback without the depth of an interview. You should work with a researcher who has experience creating reliable and valid survey questions that do not lead to biased findings. Surveys can provide a powerful argument that a market exists for your product when done at a scale allowing for statistical analysis and generalization of the results across your potential user population. You might present users with a link to view the concept or embed sketches of the concept into the survey. As survey tools evolve online, you can even include audio or video descriptions of the concept for participants to consume and then provide their feedback/complete the survey.

What Can You Do With The Data You Get From Concept Testing?

I recommend having a trained researcher guide concept testing efforts. You’ll benefit from the experience of someone with a background in designing studies and asking non-leading questions, as well as applying research findings to design recommendations based on what the data collected will bring to the team.

You’ll get different types of data depending on the method of concept testing you use. You’ll have qualitative feedback that might be good for telling the story of the product and exploring how people you spoke with see the concept evolving. You can use quantitative data from A-B testing to make decisions between multiple directions for a product and quantitative data from surveys to examine the market acceptance and prioritize features with statistical reliability if you conduct a large enough study.

Regardless of the method, once testing has validated the idea you can start designing the product, ideally going into a detailed design at the level you could then do usability testing. You can identify and prioritize features with insight from users. You can also test ideas that look beyond what an MVP will bring to life. You can create or refine a user-focused backlog of features for the product with concept testing findings.

Shortcomings Or Potential Pitfalls Of Concept Testing

Concept testing, like any research method, is not without its potential downsides or shortcomings. You can proactively account for some of these, while others might need additional research to complement your findings at a later point in the design process.

- Setting false expectations for the future.

We often run the risk of exposing users to something that either doesn’t come to fruition or won’t become realized with the same level of features or functionality that we test. For example, if you are going to let users build out on the concept after giving them an initial idea or sketch, you will need to be clear that the final product might not reflect exactly what they sketch out. Likewise, if you are sharing an idea that will have severe constraints in the short term due to limitations of your current technology, you might consider noting this or not sharing aspects of the idea that you know cannot become real for years to come. You can use concept testing to build excitement about the future product you are creating, however, you want to avoid building this up to the point where what is delivered is a disappointment. - Sometimes you need a strong story that becomes leading when walking through the concept.

If your concept is something that doesn’t exist and isn’t aligned with a system or tool someone is currently using it might be difficult to convey the idea without oversharing about how the concept will play out. I have an example of this in the second case study I share below. Essentially, you may end up telling a story that is so narrowly defined in order to convey what your product will do, your feedback will reflect how relevant the story you tell is to the users you are engaging in the testing, versus the larger value the concept might bring to users. - Usability feedback won’t happen.

Concepts aren’t meant to be of the fidelity that you are testing task completion and elements of the UI for usability. You might get some feedback on the evolution of steps in a conceptual flow, or if certain imagery or screen layout you are considering makes sense, but you won’t be in a position to refine design the same way you will be post usability testing after you’ve engaged in detailed design work. - Fidelity can throw things off.

If you use an artifact that is high fidelity it looks like a finished product. This can distract from the purpose of examining the idea, versus getting into the weeks of the look and feel of the experience. You might find participants more inclined to comment on branding or iconography than whether it even makes sense to present this experience in the context of its intended use. On the other hand, low fidelity can be too abstract for participants to provide meaningful insight. Back to the previous bullet on having a story, if you find yourself overexplaining the concept, it can become a case of you justifying your experience to a participant, and you’d be likely to introduce some type of response bias as a potential user now sees the emotional investment the creator has in the product and becomes more inclined to agree the product is useful.

Case Studies

Case Study #1: Concept Testing A Digital Kiosk For A Zoo Exhibit

I had the pleasure of serving on a design team creating a digital and physical experience conceptualized as an opportunity to enhance visitor engagement with a manatee exhibit at a major metropolitan US zoo and aquarium. We wanted to test the concept of installing touch screen kiosks in the existing exhibit space. The kiosks would have an activity asking visitors to create pro-conservation messages to email to their family and friends.

We took a low-fidelity approach to concept testing. We spent a couple of weeks on site collecting data from visitors to the zoo’s manatee exhibit. We used a felt board with velcro-backed laminated drawings and words for people to use to create messages on our low-tech touch screen. Doing this allowed us to set up the felt board in multiple places throughout the exhibit to test for location and how the kiosks might impede or enhance the flow of traffic, along with testing the actual conceptualized activity.

Here are the additional details of this concept testing:

- Concept

At the highest level, the concept was that we can encourage the scientific processes of observation, recording, and sharing what you’ve observed through an enhancement to a zoo exhibit area. More granularly, the concept was a touch screen kiosk with a digital experience designed to facilitate observation, recording, and sharing. - When/at what stage

The idea and justification for funding the project were supported with a literature review of academic research on conservation education, as well as the previous experience of the experts on the team that would assemble if the funding was granted. The initial concept was sketched out in drawings in order to secure funding from a large grant-awarding organization with a mission to promote science education and interest in careers in science.

We tested the concept with zoo visitors in the exhibit space after funding for the project was approved and the team to build the exhibit enhancement was identified. This was before any detailed design or remodeling of the exhibit area took place. - Who was involved

The team involved in the concept testing included researchers, science educators, industrial designers, digital designers, developers, zoologists, and zoo visitors. - Method

Interviews were conducted onsite in the exhibit area. We had participants engage with the prototype of the touch screen while we asked them questions. We were also able to observe visitor flow through the exhibit and how our artifact’s location might impede or enhance flow. - Artifact

Crafts: felt board, laminated pictures of manatees, water, vegetation, and other relevant manatee habitat features with velcro on the back, laminated words for visitors to use to create messages under their pictures on the felt board.

Reflection

I view this as one of the most successful concept testing efforts I’ve been a part of. We executed the testing well, and more importantly, we learned a lot to help us move forward with the idea that would eventually become an integral part of visiting the manatee exhibit.

We interacted with visitors in their context as part of the testing. Testing the concept in the actual space where it would exist allowed us to understand the impact of installing kiosks in the space. We learned from this how much of a potential negative impact on visitor flow the kiosks would have, and where we might best place the kiosks based on observed visitor flow through the exhibit.

The tangible representation of the concept allowed visitors to interact with it in a way similar to a touch screen. We learned how visitors envisioned the experience, including identifying a number of expectations our concept would not meet.

One example was the freedom to create any message they wanted versus being given preselected lists of words to choose from. The product owner for the concept had concerns we could not allow people to create messages that might be offensive. We attempted to remedy this on our final design by including a message that allowed the user to enter their own email into the message as well.

We included a note that if they wanted to continue the conversation later in a less structured way, they could ask the person they were sending the note to reply to them. We also included this request as a predefined sentence that users could add to their message “Let’s keep the conversation going! Please reply to this email and I can share more with you when I get home.” (This was prior to ubiquitous smartphones.)

Ultimately testing was successful because we were working with a group that envisioned bringing visitors and experience informed by their needs and expectations. UX was not just a process, but a philosophy embraced by the team. Concept testing allowed us to shape the final design well before the materials were fabricated, screens were designed, or code was finalized.

Case Study #2: Concept Testing A Digital Platform For Online Financial Management Tools

A large international financial advisory wanted to create a new product that would combine multiple existing applications and bring new features to advisors using their services. The idea was simple yet the execution was going to be complex. The client wanted our team to explore the needs and pain points of users of the current applications, understand what gaps exist between the current applications and the needs of the users, and identify potential problems with bringing the concept to life and sunsetting the individual applications.

- Concept

Initially, an idea that then became wireframes after we conducted initial interviews with stakeholders who were also infrequent end users. - When/what stage

From a UX perspective, we were in the process of doing discovery interviews with stakeholders and potential users. We then mocked up the concept using a very constrained story to walk people through how the experience might unfold under a specific use case. - Who was involved

We had what might be considered a full product team engaged, we had a team of researchers, UX designers, and developers. We had multiple product owners from the existing products involved, as well as the owner of the yet-to-come-to-life product. - Method

We conducted remote interviews and screen sharing of a clickable prototype to engage stakeholders and potential end-users. - Artifact

We created a series of screens to highlight key features and steps of a couple of workflows we identified from stakeholders as critical to the success of the product. Due to the complexity of the idea, we felt it was important to create a very streamlined story to showcase exactly what the product was meant to accomplish in those scenarios.

Reflection

This example of concept testing was not as focused on meeting the user’s needs as my previous example. While we were able to inform and improve the experience with the insights we gained, it became clear that a large part of our endeavor was to foster buy-in from high-level stakeholders who were key decision-makers and influencers at the organization. I’m not saying this is a bad thing, but it led to us interacting with a different set of research participants than we would have preferred if we were focusing on meeting the needs of users. I understand, and you likely do as well, there are many factors at play when an organization is making a determination to fund a new product.

Our client provided us with a list of required stakeholders to participate in the interviews and testing. We found out these stakeholders were more high-level than what would be considered an everyday user of the product. The client was pleased with the list because they wanted to raise awareness and buy-in of the concept at the top levels in their organization. We found less value in having these high-level stakeholders providing feedback on the concept and the experience because they were far removed from understanding some of the issues with the current tools, as well as the exact processes that were core to the purpose of the concept.

Upon reflection, I realize this testing was not ideal, but useful as an example of what to watch out for when setting up concept testing. I’m not sure the effort was worth the outcome, which yielded us little useful information relevant to end-users. We did the testing at the right time and with the right intention, but with the wrong audience. Our findings uncovered concerns of high-level stakeholders and salespeople around how they envisioned the use of the tool by others, or how they thought potential customers that might access the tool would respond. We reflected our concern that we needed end-users who were closer to the issues the concept was meant to resolve in our report out to the client. Many of our findings and recommendations for the next steps included getting these ideas and designs in front of actual end-users.

We were still able to uncover valuable insights, but perhaps we would have gotten much more in-depth on how the concept could play a role in the day-to-day life of users if we’d had a chance to speak with those types of end-users. We were able to identify the critical role of data visualization and show where data come from for this group. The concept was meant to help with making financial decisions and responding to real-time market conditions, so having trustworthy, easy-to-digest information was deemed critical. This allowed us to expand the role of data visualization as well as test some novel ideas for visualizing data, prior to moving into detailed design.

We also captured a number of concerns over what would happen with the legacy systems and training/education on the new system. We felt this made sense and aligned with the characteristics of the stakeholders we’d spoken to: many of them had invested budgets or sold the existing tools, and they would need to start finding solutions on how to communicate the transition to the new consolidated tool to their teams or clients as soon as possible.

Conclusion

Concept testing is a blend of market and UX research, two disciplines that share many methods in common. You shouldn’t consider it anti-UX to also explore topics related to market acceptance. After all, what good is a usable product if it serves no purpose or doesn’t have any meaningful sized market willing to adopt it?

Any experience starts as an idea — a concept — and we are in line with the philosophy of putting users first when we take our ideas out to the end-user for feedback at the conceptual stage. We can avoid costly errors in our design if we determine direction upfront through user research in the form of concept testing. You also make yourself open to gaining new insight and evolving your concept in directions you were not thinking of prior to engaging a broader group — including users — to provide feedback on the idea.

Further Reading

- How To Manage Dangerous Actions In User Interfaces

- The Importance Of Graceful Degradation In Accessible Interface Design

- Long Live The Test Pyramid

- The Fight For The Main Thread

Register Free Now

Register Free Now Celebrating 10 million developers

Celebrating 10 million developers SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App

SurveyJS: White-Label Survey Solution for Your JS App